This fall, as part of the worldwide Bernstein at 100 celebration, the theory department presented “Bernstein as Teacher: Exploring the Language of Music,” another installment in our Musical Conversations series in collaboration with CU on the Weekend. To commemorate this 10th issue of Think Theory! we feature two articles, drawn from the lecture.

BERNSTEIN, MUSIC, AND LANGUAGE

Bernstein’s first three Charles Eliot Norton lectures (1973) explore analogies between music and language. Taking his cue from linguistics, Bernstein discusses phonology in the first lecture, syntax in the second, and meaning in the third. In his lecture on syntax, he posits a relation between musical dimensions and parts of speech, suggesting that melody forms the equivalent to a musical noun, harmony an adjective, and rhythm a verb.

Bernstein claims it would be possible to expand upon these ideas. However, it might be difficult to address, for example, what properties a musical preposition might possess. Part of the problem is that his three linguistic categories (noun, adjective, verb) map on to the three primary dimensions of music (melody, harmony, and rhythm). From there it is difficult to sustain the linguistic analogy.

Schema theory, derived from cognitive theory, offers an alternative view. According to Jean Mandler, a schema is “a mental structure formed on the basis of past experience with objects, scenes, or events, and consisting of a set of (usually unconscious) expectations about what things look like, and/or the order in which they occur” (Stories, Scripts, and Scenes: Aspects of Schema Theory, 1984). One such schema is Joseph Campbell’s notion of the hero’s journey: although the details may differ, numerous heroic epics follow similar stages in a similar order, with obstacles and adversity eventually overcome.

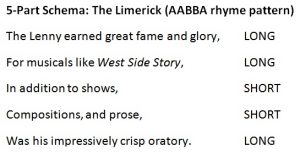

Musical organization offers schemas (or schemata) as well, setting up expectations of particular events that occur in a particular order. Musical phrases, for example, often come paired in specific ways, or sometimes are grouped in threes or fours. Five-part groupings are akin to limericks in some details of design, especially with their long/long/short/short/long groupings.

The following audio excerpt picks up in a discussion of five-part groupings, concluding with an example from the first movement of Beethoven’s piano sonata in F minor, Op. 2, No. 1.

Keith Waters, the limerick, and Beethoven

–Keith Waters

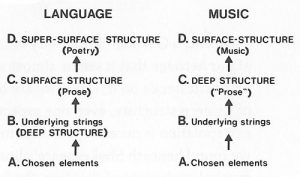

In his second Norton lecture (viewable here), Bernstein employs Noam Chomsky’s notion of universal grammar to show how quotidian prose, through various transformations, becomes more elaborate and complex. The ultimate result is art, namely poetry: abstract, aesthetic, metaphorical. Music is similarly abstract, aesthetic, and metaphorical, and while Bernstein considers all music already as art, he suggests a kind of “musical prose,” somewhat banal and workaday passages of music without much expressivity and imagination. He diagrams the analogy so:

Like language, musical prose can be transformed into art. Bernstein demonstrates this by turning a Charles-Louis Hanon piano drill into a fugue. The following audio montage is a summary in Bernstein’s own words.

Bernstein elaborates a Hanon exercise

The analytical method of Austrian music theorist Heinrich Schenker (1868-1935) mirrors Bernstein’s argument, but in reverse: undoing the transformations reveals rather generic and rudimentary pitch activity.

This edited excerpt from an analysis by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping shows the final measures of a piece reduced to long-term arpeggiations and stepwise fragments. Do you recognize the tune? It’s “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The parallel presentation shows how the notes correspond, so the distilled version will sound somewhat like the original tune. Could you identify a familiar melody from its “musical prose” version? Try it!

Philip Chang plays a musical skeleton

What you heard was musical prose gradually transformed into “America.” The process is similar to Bernstein’s fugue, except that instead of using another piece as a source of elaboration, here the musical prose is a simplified version of the music itself! In this way, we can hear and see music as having a “skeleton,” as C.P.E. Bach put it, which organizes the decorative surface. Schenkerian analysis shows that certain fundamental structures underlie numerous tonal pieces, echoing Bernstein’s belief in Chomskian universality.

–Philip Chang

STUDENT NEWS

Meet our current students Jacob Eichhorn, Devin Guerrero, and Rebecca Hamel.

Jacob Eichhorn (M.M. Clarinet Performance, 2015) serves as TA for sophomore aural skills. He has also taught freshman aural skills and an elective non-major theory course during his time at CU Boulder. Jacob is currently working on his master’s thesis, which applies a narrative interpretation to Leoš Janáček’s Mládí (“youth”). In a letter to his paramour, Janáček writes about the piece, “I have written a sort of memoir here”; with this as a jumping-off point, Jacob takes up an autobiographical approach in his reading of Mládí. In A Theory of Musical Narrative (2008), Byron Almén suggests that “[n]arration involves the coordination of multiple elements involving different mechanisms of meaning and different levels of focus or temporal scope.” The coordinated musical elements that inform Jacob’s interpretation comprise motivic transformations, pitch collections and collectional shifts, metric dissonance, instrumental agents, topic, affect, and the defiance of expectation.

Upon completion of his master’s degree in music theory (anticipated 2019), Jacob plans to stay an additional year at CU Boulder to complete the remaining final projects of his doctoral degree in clarinet performance and pedagogy.

Devin Guerrero graduated from the University of North Texas (B.M. in Music Education, B.M. in Music Theory) in 2012, studying with Stephen Slottow, Danny Arthurs, and Gene Cho. Devin’s undergraduate colloquium research applied Schenkerian analysis to jazz tunes, specifically addressing the paradox between goal orientation and circularity in Thelonious Monk’s “Ruby, My Dear.” He also studied language abroad in Leipzig, Germany and continues honing his German annotating and translating portions of Schenker’s Der Tonwille. Prior to arriving at CU, Devin worked as a high school orchestra director in Austin, TX. His time there helped him realize his passion for classroom instruction and appreciation for the administrative side of fine arts. He currently works as a teaching assistant for the course Music Theory for Non-Music Majors, and gives private bass and piano lessons off campus. Devin maintains his studies in jazz analysis, focusing on bebop and post-bop artists, as well as exploring permutations of classical compositional devices in popular music from the Beatles to now.

Rebecca Hamel is a first-year master’s student at CU Boulder. She holds a B.M. in musical studies and trombone from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam (2017). Currently, Rebecca serves as a TA for the theory department and is teaching Aural Skills I this semester. In addition to teaching, classwork, and research, Rebecca keeps up with the trombone by continuing to take lessons and perform in university chamber groups.

Rebecca’s main interests center on rhythm and form in two areas: Latin American music, and Schubert’s Lieder. During her undergraduate career, she played in the Crane Latin Ensemble, a NY-style salsa band that traveled frequently, visiting New York City and Cuba during her time with the group. Getting to experience Cuban culture and musical traditions first-hand continues to inspire her research. Regarding Lieder, Rebecca is exploring the role of poetic scansion in the creation of Schenkerian graphs of these works. Outside of the university Rebecca is involved in outreach to community arts centers and teaches basic musicianship skills (such as theory and aural skills) to practicing adult musicians from a variety of backgrounds.

ALUMNI NEWS

Clay Downham (M.M., 2018) presented a paper at the 2018 national meeting of the American Musicological Society and Society for Music Theory, entitled “Conceiving the Concept: Style and Practice in Eric Dolphy’s Applications of George Russell’s Lydian Chromatic Concept.”

Michael Furry (M.M., 2013) won the 2018 Utah State Flat Pick Guitar Championship, placed second in the 2018 Utah State Finger Picking Guitar Championship, and second in the RockyGrass Flat Pick Guitar Championship. He is the incoming director of the bluegrass ensemble at the Lamont School of Music at the University of Denver.

Landon Morrison (M.M., 2012) is completing his doctoral studies at McGill University (Montreal). In the summer of 2018, he received a three-month grant to undertake archival research at the Paul Sacher Institute in Basel, Switzerland, studying the music of Gérard Grisey, Kaija Saariaho, and Jonathan Harvey.

John Peterson (M.M., 2011) presented a co-authored paper at the 2018 national meeting of the Society for Music Theory, entitled “Defying Brevity: Expansion Above the Phrase Level in Musical Theater.”

Alan Reese (M.M., 2013) finished his Ph.D. degree from the Eastman School of Music this year and was hired as a faculty member at the Cleveland Institute of Music. He presented a co-authored paper at the 2018 national meeting of the Society for Music Theory, entitled “The Riemannian Klangnetz, the Doppelklang, and Their Applications.”

UPCOMING EVENTS

Colloquia (academic presentations)

Imig Music Building, C-199 (Chamber Hall)

“Analysis and Performance in Bach’s Keyboard Music: A Conversation with Robert Hill”

Header image by Alena Koval