Expectation, Convention, and Surprise in Karl Maria von Weber’s Clarinet Concerto, Op. 73

by Georgia Hastie

In the second movement of his second Clarinet Concerto, Op. 73, Karl Maria von Weber has included various unexpected musical occurrences which, while going against convention, also help to add interest and expression to the piece. In doing so, this may affect how the piece is performed. These musical “surprises” can be studied through three different lenses: melody, harmony, and form.

A version of the main theme of this movement has been rewritten to contain no unexpected melodic occurrences.

Although this may sound perfectly normal to someone who has never heard the piece before, a significant difference can be heard when the melody is played as written by Weber.

As is apparent when comparing the two versions, Weber has written an A flat in his opening melody, which is not part of the key. The addition of this chromatic pitch is something that the audience wouldn’t necessarily expect, which may influence the performer’s interpretation of this line, such as putting more emphasis on the A flat in bar 4 by giving it an accent, or leaving slightly more space before the A flat is played, which heightens the suspense leading into the surprise of this non-diatonic note. In the descending chromatic line a few moments later, there is more directed motion which in turn might cause a performer to add more of a crescendo through the chromatic line directed towards the A flat. This kind of chromaticism might also reveal something about the relationship between body use and gesture and expression in the music. For example, a performer might physically lean into the A flat in bar 4 more than they would if the A flat were not there.

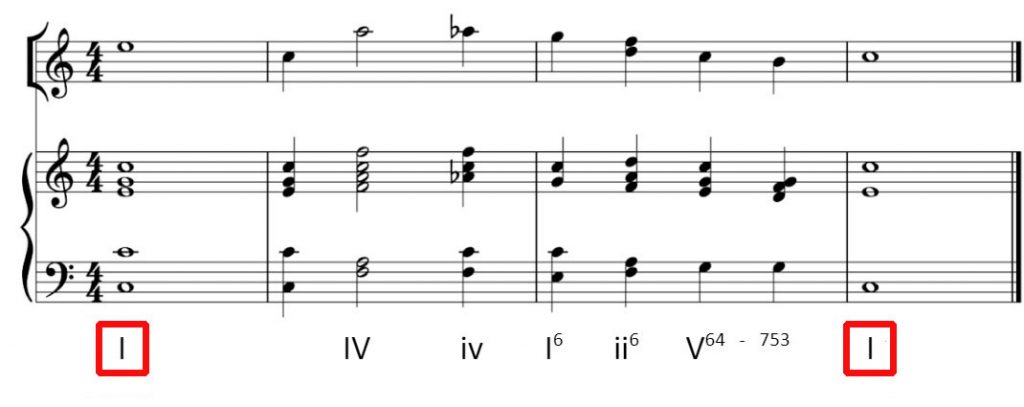

Another way in which Weber adds surprise to his music is through harmony. An excerpt from the end of the A section—where Weber has brought back the main melody—has been recomposed so that its harmonies are as simple as possible.

As can be seen in the harmonic reduction in Figure 1, this rewritten version generally follows the standard convention of a four-bar phrase containing a simple Tonic-Predominant-Dominant-Tonic chord progression.

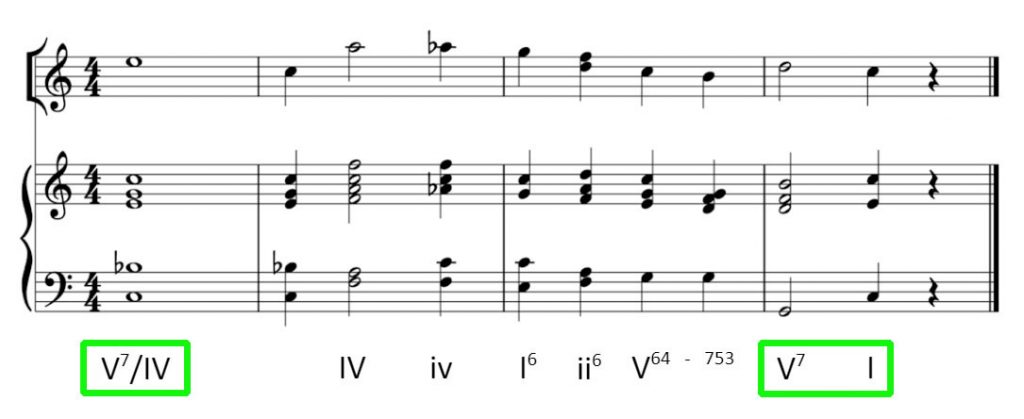

A second recomposed version of this excerpt includes slightly more of the harmonic interest that happens in the original.

Instead of a tonic chord at the beginning, the first chord contains a chordal seventh, making it a V7/IV (see Figure 2). Additionally, the V7 chord at the end is prolonged for 2 extra beats before resolving to I.

It’s apparent that changing just one note in the first chord creates quite a different feeling to that line. Similarly to the melodic surprises, it may cause the performer to lean more into that note, to play at a louder dynamic, or to shape the line differently, such as adding a crescendo through the pickups so as to arrive at the V7/IV with more volume, as well as adding a slight accent to the first note of that bar. Time might also be taken by the orchestra right before these pickups in order to create even more suspense leading into the V7/IV chord, since the pickups lead the listener to expect the familiar melody and its supporting tonic harmony, but instead arrive on a dominant seventh chord.

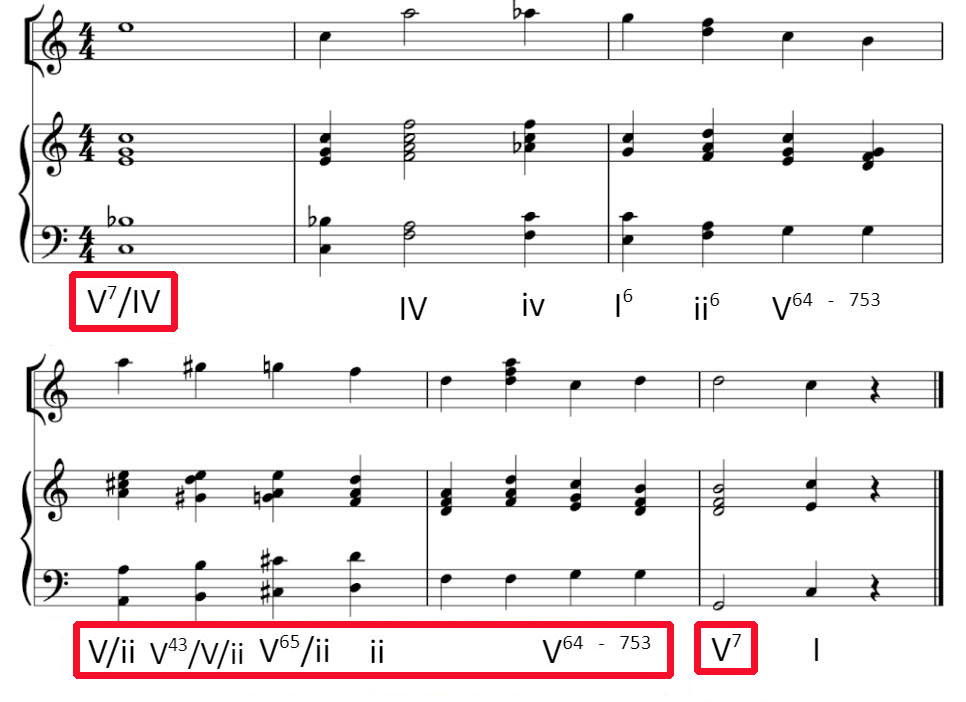

Finally, here is Weber’s actual version.

Weber has inserted two extra bars containing a progression of applied chords, stretching the phrase to 6 measures, and delaying the ending of this section.

Like most places where Weber adds unexpected ideas to his work, these unexpected additional two bars should be brought out more. Even if playing from a completely unedited copy, an expressive performer would still intuitively bring out this unexpected section by playing a sforzando or an accent. This speaks to the element of surprise and the ways we highlight these nuances in performance.

Finally, another way in which Weber strays from convention in this movement involves the form itself. This movement mostly follows a typical ternary, or ABA, form. A ternary form consists of three parts, with the second part contrasting to the first, and the third being the same or similar to the first. However, in the middle of this ternary form, after the B section, Weber has added an extra section, which most have come to call the “chorale section.” This “chorale” section is very different in style from both the A sections and B section. A recording of the B section and part of the chorale section can be heard in this video.

The sparse instrumentation of the horn trio accompaniment paired with a change in key and a softer dynamic invites the performer to portray different affects compared to the B and even the A sections. For example, a performer might play more quietly and with less dynamic contrast, as well as with a warmer tone to match that of the horns.

Furthermore, the chorale section can create suspense in the piece by causing the listener, who would likely expect the return of the A section after the B section ends, to instead wait, wondering when or if the main theme will return.

Overall, while looking at unexpected occurrences in melody and harmony in this specific piece, it was almost always the case that these unexpected things should be brought out more in performance, through dynamic shaping, accents, or even body movement. As for how the overall form of a piece might influence one’s interpretation, it does this in a broader sense, such as in tone quality, overall dynamics, articulation style, and mood or character.

Daniel Silver, clarinet professor at CU Boulder, once said, “Great music has balance between predictability and surprise.” Through analysis of this piece, it’s evident that by occasionally going against convention and including surprise in his work, Weber has succeeded in taking a piece that would surely be quite lovely and making it into something far greater.