“Keep Moving”: An In-Depth look at Writing for a Jazz Big Band and Analyzing the Works of Maria Schneider, Jim McNeely, and Pat Metheny

by Ben Thompson

“Keep Moving,” an original composition written to be played by jazz big band, was a long project of mine that lasted many months and made me incredibly happy and incredibly depressed every minute of every day. I called this composition “Keep Moving” simply because that is how I felt at this time: “If I want to make it through the year, I need to power past all these pent-up emotions and keep moving.”

While writing this piece was an incredible endeavor for me, one of the best parts of it was analyzing modern jazz musicians and integrating techniques they used into my own composition. These musicians, Pat Metheny, Jim McNeely, and Maria Schneider, all have incredible works for large jazz ensembles (over 10 instruments). I implanted techniques they used into my own composition to give my work more of a modern sound with a sense of flow from section to section.

In an attempt to escape the common practice of writing a jazz melody, I decided to write “Keep Moving” without a common practice jazz form (a typical jazz composition, e.g., “Summertime” by George Gershwin, will be structured in a popular song form most commonly seen as 32 bars with an AABA or ABAC melodic structure). I ended up writing “Keep Moving” with two different large sections (A and B respectively) with different melodies and chord changes. This is significantly more different than what people normally think about when they hear a jazz composition. In addition to these two sections that could each be called melody sections, I was able to add a third section, C, with the intent of giving the song room to breathe.

We can hear this in Audio Example 1, where the alto saxophone solo, after having a large chordal transition section, starts much more relaxed than the previous section’s energy level.

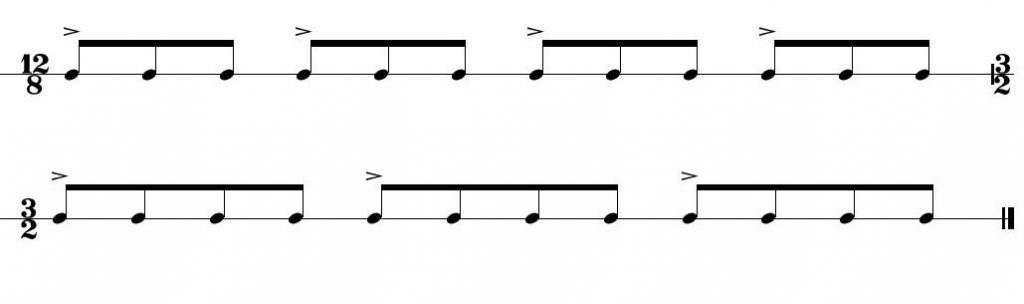

One of the ideas I had that inspired much of my work in this piece was metric modulation as derived from Pat Metheny’s “The Way Up: Opening.” During my lecture recital, I showed how metric modulation works with the help of the audience.

In Picture Example 1, metric modulation regroups a steady pulse (eighth notes) to create a new tempo in a new meter. We can see that, in video example 1, metric modulation is very hard to initially wrap your head around as shown by the audience’s difficulty in maintaining a steady pulse when the drummer (Colin Hill) switches to the new metric modulated rhythmic groove.

Maria Schneider inspired me in a much different way than Pat Metheny. The form in her songs had a large influence on me. What she does is she writes a solo section with different chords than the initial melody. This is especially apparent in her song “Dance You Monster to My Soft Song” where after the initial aggressive melody hits you, we are greeted by a very subtle guitar solo at a much lower energy level with a new set of chord changes.

This is a big change from the popular song forms of George Gershwin’s “Summertime” and Cole Porter’s “I Love You,” just to name two. While this is very apparent in Schneider’s piece (Audio Example 2), we can hear it in “Keep Moving” in Audio Example 1 where, after a loud impact from the horns, there is a large drop in energy for the alto saxophone solo.

Jim McNeely inspired me in a different way from Pat Metheny but similarly to the way that Maria Schneider inspired me. I was especially interested in the way that McNeely used his soli sections. Since the birth of jazz big band, the “sax soli” has been a fundamental staple of all jazz big band music. Typically done over the chord changes of the melody, the saxophone section will play a harmonized written–out line. The harmonization moves in similar motion with the same rhythmic pattern the entire way through. Count Basie is the best example of this, since all of his songs were written with this idea of a sax soli in mind (the chart for “Basie Straight Ahead” was made by one of his sax players, Sammy Nestico).

Jim McNeely sought out a completely different idea of a soli. For one, he didn’t limit it to only the sax section, and he decided to use it as a second melody that builds on itself the more instruments you add to it. Eventually, a counter line to the soli is introduced to make the song explode with energy. It really shows Jim McNeely’s creative brilliance upon analyzing it in acute detail. In Audio Example 3, we can hear how Jim McNeely’s does this in his composition “Extra Credit,” while Audio Example 4 is my version of Jim McNeely’s technique.

Even though I was inspired by all of these great musical elements from Metheny, Schneider, and McNeeley, I, much like any composer, am not one hundred percent satisfied with my work. After writing the piece, there are several aspects I would like to improve on. One is length: “Keep Moving” is around 17 minutes long. That might be too long and there might be sections I could take out to make it a more normal length. Also, I need to consider the difficulty of this song. While CU’s Concert Jazz Ensemble (CJE) did a fantastic job playing this song, they only had three rehearsals to read through this chart, and it was incredibly difficult for them to get the song together in that amount of time. I am quite happy with how the piece came out and am satisfied with it as one of my first big band compositions. You can listen to the full recording of CJE playing “Keep Moving” below.