Freedom in Barney Childs’s “Recitative”

by Yutaro Yazawa

When J. S. Bach wrote music, he was seemingly concerned only with getting the notes written down, often neglecting dynamics or phrase markings. Much later, when Gustav Mahler was writing, he made sure almost every note had some sort of notation around it, ensuring the music would be performed exactly as he heard it. In the past few decades, composers have challenged this trend of more control over their music, by writing pieces that leave fundamental aspects of the music up to the performer, such as the ordering of sections, the length of time a particular part is to be played, what notes to play, or even instrumentation. Some feel however, if taken too far, that the lack of defined structure can take away from the legitimacy of the music: what’s the point if anything goes?

One composer that walks this line between being specific and free is Barney Childs. He was born on February 13, 1926 in Spokane, Washington, and died on January 11, 2000. Trained as a literary scholar, Childs taught himself music until he studied under Leonard Ratner, Carlos Chávez, Aaron Copland, and Elliot Carter in the 1950s. Childs taught English literature at the University of Arizona from 1956 to 1965, before becoming Dean at Deep Springs College (1965–69). He then was composer-in-residence at Wisconsin College Conservatory for one year (1970) before settling down at the University of Redlands, where he taught composition and music literature. Utilizing his background in literature, Childs was very prolific in writing about his and others’ music as well as literature and poetry.

Sonata for solo trombone

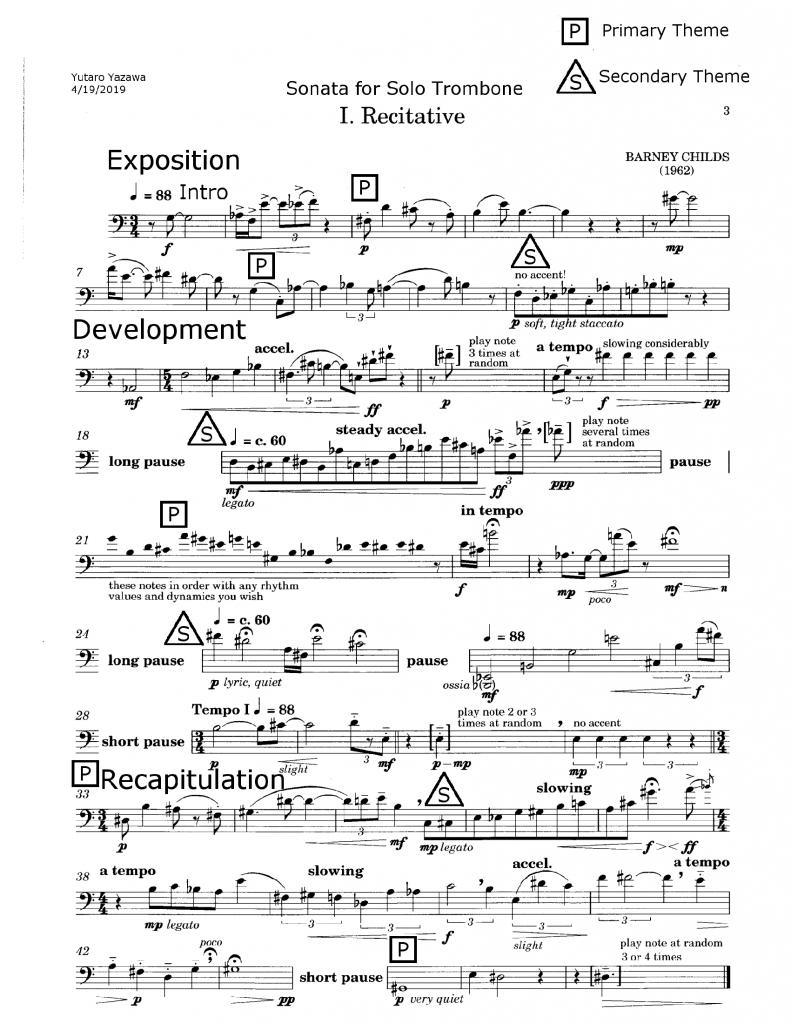

Let us look at a piece that displays his ideas of freedom and control: his Sonata for Solo Trombone. First, an overview of the piece. A sonata implies a fairly strict form, and has been used widely for hundreds of years. However we will see that Childs has used this form in an unconventional way, in combination with other forms to challenge the perception of a sonata.

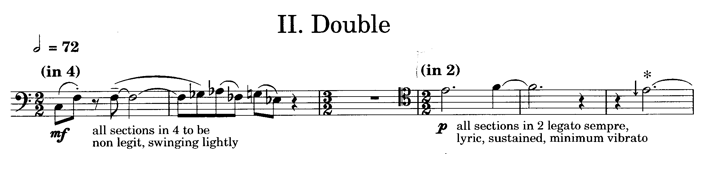

The first movement will, by definition, be in sonata allegro form, and as it is the focus of this essay I will discuss it in detail later. The second movement could either be a slow movement or a dance. Childs has combined them, by utilizing a double variations form. A double variations form is a theme and variations based on two themes.

The first theme Childs uses is swung, referencing jazz’s ties to dance music. The second theme is in half time from the first theme, and thus feels slow, the aspect of the other type of middle movement in a sonata form.

The last movement in a sonata is usually fast, and can employ rondo form. A rondo form is characterized by the repeat of an A section interspersed with contrasting material. Childs has marked the movement exuberant. However, he has done something unusual with the form, by providing multiple variants of each section at once, and letting the performer choose at will which variant to use in each section. Childs has specified that the rondo form must be maintained, but the exact implementation of it is up to the performer (e.g. the performer can play ABA…, ABACA…, ABCACDA…, playing whatever variant of each section they choose).

This is a good example of how Childs has given a little freedom to the performer to choose the form, but has kept control over the notes and rhythms, creating an interesting fusion between composition and improvisation.

I. “Recitative”

The first movement of Childs’s Sonata is marked Recitative. A recitative is a genre with its origin in opera and oratorios from the 17th century, where a solo singer imitates dramatic speech through song. Its function was to further the plot of an opera, and to contrast with the arias (which were more concerned with each character’s emotions). Some typical aspects of recitative include a through-composed nature, irregular meter and harmonic movement, changing tempo or rubato, and minimal accompaniment by the orchestra. The accents of recitatives also follow the stress patterns of the language, and vary drastically between different countries. Childs uses these, as well more modern techniques categorized as indeterminacy, or aleatory, in his Sonata. I described aleatory without defining it earlier, as music where fundamental aspects of the music are left up to the performer. Childs uses these techniques to further the imitation of recited speech, more than would be possible with conventional means.

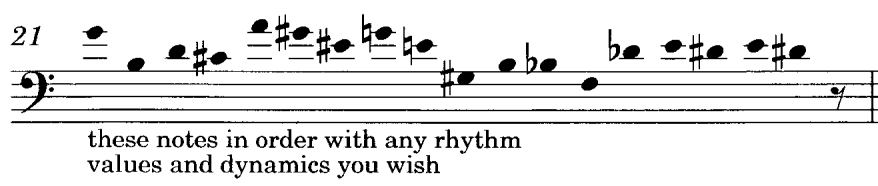

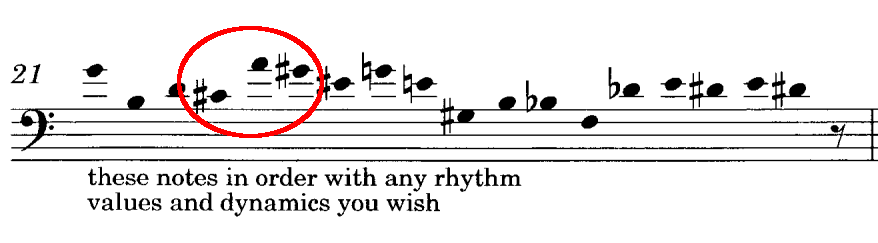

The clearest example of indeterminacy in this movementis in m. 21, where Childs has written a complete measure with pitches, but no rhythms or dynamics. He has instead given the performer freedom to choose whatever dynamics and rhythmic values they fancy.

This I feel is a similar effect to someone giving a speech. They know what they are going to talk about (pitches), but they don’t always know the precise wording or phrasing beforehand (rhythms and dynamics). Often speech is very improvisatory, and this particular measure in this piece mirrors that nature very well.

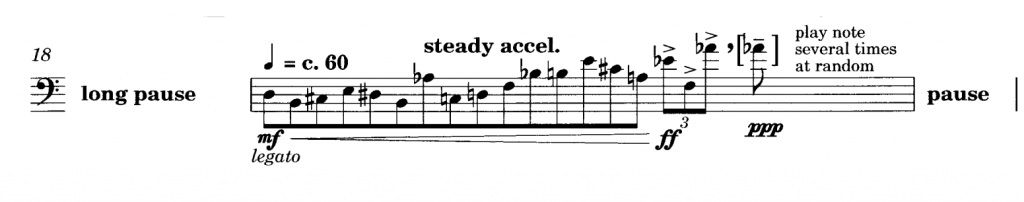

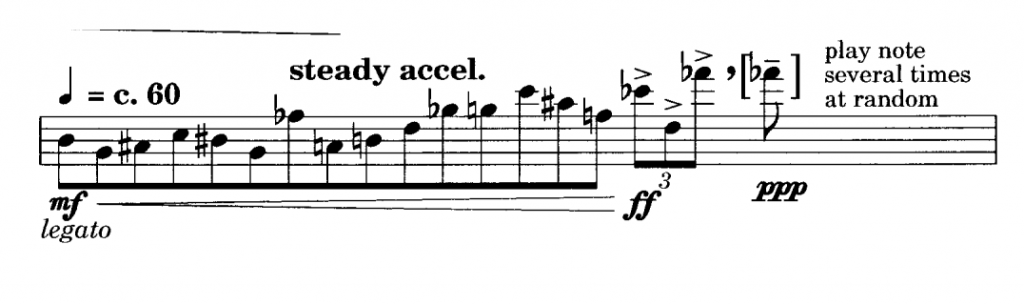

Childs also uses another type of aleatory in his music where he brackets a note and indicates “play note several times at random.”

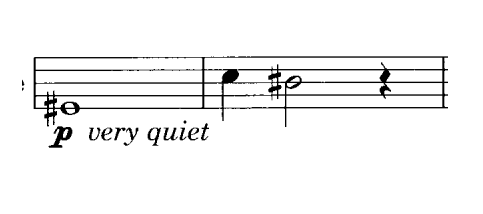

These randomly repeated notes occur after a build-up of energy through rising pitch and crescendos. They create musical tension by contrasting starkly with the preceding build-up. Also, because they are rhythmic yet without a defined meter or pulse, they disorient the listener and leave them expecting closure. Functionally, this is similar to a question mark in speech, where there is separation and yet the question resolves into an answer. Here the “answers” are the same pitch as the “questions” and are repeated in a metered fashion, providing resolution. The question-like quality of the “random notes” can especially be exploited at the end: for example the performer could play the last measure as if they are trailing off, unsure of the conclusion, or as a rhetorical question, leaving the audience pondering.

One last use of indeterminacy in this first movement is Childs’s use of pause in his music. There are plenty of examples where silence is used in music; however, Childs uses it in an interesting way, where instead of writing out measured rests, he simply leaves a space and the word “pause.” An example can be seen in the previous excerpt.

Childs has compared aleatoric music to action-painting. He states that one cannot tell whether something is written or not just by listening to it, but the process by which that music was made is what creates value.[1] This is especially true in terms of these “rests,” because the listener cannot discern whether the rests are measured or not. However to the performer, these rests force them to react to the music through the rests, and decide when to move on, very similar to how public speakers will use rests in speeches for dramatic effect. The speakers do not count how long they have remained silent, but rather judge through what they feel “is right.”

Form

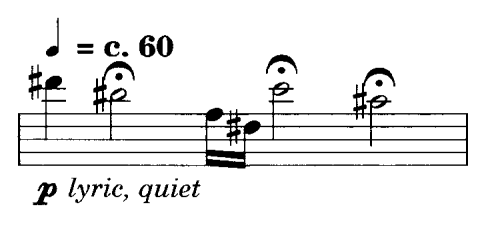

Let us discuss the form of this first movement. A sonata form can be split into three main sections: the exposition, the development, and the recapitulation. The exposition mainly presents two themes of contrasting material. Our first theme begins in measure 3.

It is characterized by a legato style, and an important feature of this melody is an ascending minor sixth followed by a descending half step. The second theme appears in measure 11.

It contrasts the first theme with a machine-like staccato, and is characterized by pairs of thirds linked by half steps.

Now, these two themes can be taken through the development. Because of the atonal nature of the work, Childs cannot do what is typical, and transpose the themes through various keys, but he transforms them in other ways.

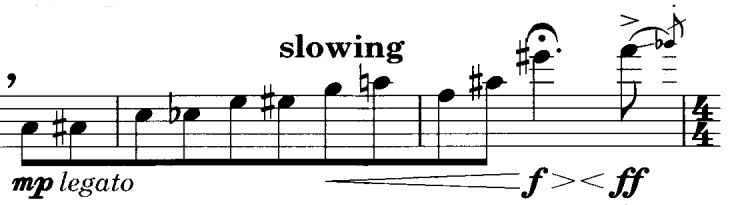

In measure 19, Childs uses the third-half step chains of the second theme, but now in a legato style, and combines it with a crescendo/accelerando gesture (this passage has been heard before, in explaining aleatory).

This leads us into measure 21, where Childs has nested the primary theme (minor sixth–half step) inside the string of pitches. This may lead the performer to bring out these three notes in creative ways, as the rhythms and dynamics are up to the performer at this point.

In measure 25, we see the pairs of thirds from the secondary theme, but this time connected by larger intervals. Again the mechanical nature of the second theme has been taken over by a much calmer, lyrical style.

The beginning of the recapitulation is very clear in many sonatas, and this piece is no exception. At measure 33, an almost exact repeat of the primary theme in the exposition appears (albeit starting on a different note).

This is followed immediately by a restatement of the secondary theme. This restatement is not nearly as similar to the one presented in the exposition, though. Usually, in a sonata form, the secondary theme is in the dominant key in the exposition, and in the tonic key in the recapitulation. Perhaps Childs is alluding to this by transforming the secondary theme so much. The theme is again merged with a crescendo gesture, but this time it is paired with a slowing down instead of an accelerando. Childs has also flipped the relationship between the notes, so that instead of having pairs of thirds connected by half step, he has pairs of half steps connected by thirds.

Finally, after a brief excursion, Childs has the first three notes of the primary theme again to close this movement. Because it is so sustained and quiet now, it almost bears a solemnness, as if a tragedy has struck.

Performance

Here is a complete performance of the first movement of Barney Childs’s Sonata for Solo Trombone. An annotated score showing the movement’s form can be found below.

Bibliography

“Barney Childs.” American Composers Alliance. Last modified February 19, 2009. https://composers.com/barney-childs.

“Childs, Barney.” Grove Music Online. Accessed February 8, 2019.

Childs, Barney. “Indeterminacy and Theory: Some Notes.” The Composer 1/1 (1969): 15-34.

Karlins, William. “Freedom and Control in Twentieth-Century Music.” TriQuarterly 52 (Fall 1981): 244-259.